1 - Fixed-Tilt Yearly Results#

This jupyter journal will walk us through the creation of the most basic fixed-tilt simulation possible with bifacial_radiance. We will simulate a 1-up landscape system over a white rooftop.

Steps include:

Create a folder for your simulation, and Load bifacial_radiance

Create a Radiance Object

Set the Albedo

Download Weather Files

Generate the Sky

Define a Module type

Create the scene

Combine Ground, Sky and Scene Objects

Analyze and get results

Visualize scene options

This jupyter journal will walk us through the creation of the most basic fixed-tilt simulation possible with bifacial_radiance. We will simulate a 1-up landscape system over a white rooftop.

Steps include:

Create a folder for your simulation, and Load bifacial_radiance

Create a Radiance Object

Set the Albedo

Download Weather Files

Generate the Sky

Define a Module type

Create the scene

Combine Ground, Sky and Scene Objects

Analyze and get results

Visualize scene options

1. Create a folder for your simulation, and load bifacial_radiance#

First let’s set the folder where the simulation will be saved. By default, this is the TEMP folder in the bifacial_radiance distribution.

The lines below find the location of the folder relative to this Jupyter Journa. You can alternatively point to an empty directory (it will open a load GUI Visual Interface) or specify any other directory in your computer, for example:

testfolder = r’C::nbsphinx-math:`Users`:nbsphinx-math:`sayala`:nbsphinx-math:`Documents`:nbsphinx-math:`RadianceScenes`:nbsphinx-math:`Tutorials`:nbsphinx-math:`Journal`1’

[1]:

import os

from pathlib import Path

testfolder = Path().resolve().parent.parent / 'bifacial_radiance' / 'TEMP' / 'Tutorial_01'

# Another option using relative address; for some operative systems you might need '/' instead of '\'

# testfolder = os.path.abspath(r'..\..\bifacial_radiance\TEMP')

print ("Your simulation will be stored in %s" % testfolder)

if not os.path.exists(testfolder):

os.makedirs(testfolder)

Your simulation will be stored in C:\Users\sayala\Documents\GitHub\bifacial_radiance\bifacial_radiance\TEMP\Tutorial_01

This will load bifacial_radiance and other libraries from python that will be useful for this Jupyter Journal:

[2]:

try:

from bifacial_radiance import *

except ImportError:

raise RuntimeError('bifacial_radiance is required. download distribution')

import numpy as np

2. Create a Radiance Object#

[3]:

# Create a RadianceObj 'object' named bifacial_example. no whitespace allowed

demo = RadianceObj('tutorial_1',str(testfolder))

path = C:\Users\sayala\Documents\GitHub\bifacial_radiance\bifacial_radiance\TEMP\Tutorial_01

This will create all the folder structure of the bifacial_radiance Scene in the designated testfolder in your computer, and it should look like this:

3. Set the Albedo#

To see more options of ground materials available (located on ground.rad), run this function without any input.

[4]:

# Input albedo number or material name like 'concrete'.

demo.setGround() # This prints available materials.

Input albedo 0-1, or string from ground.printGroundMaterials().

Alternatively, run setGround after readWeatherData()and setGround will read metdata.albedo if available

If a number between 0 and 1 is passed, it assumes it’s an albedo value. For this example, we want a high-reflectivity rooftop albedo surface, so we will set the albedo to 0.62

[5]:

albedo = 0.62

demo.setGround(albedo)

Loading albedo, 1 value(s), 0.620 avg

1 nonzero albedo values.

4. Download and Load Weather Files#

There are various options provided in bifacial_radiance to load weatherfiles. getEPW is useful because you just set the latitude and longitude of the location and it donwloads the meteorologicla data for any location.

[6]:

# Pull in meteorological data using pyEPW for any global lat/lon

epwfile = demo.getEPW(lat = 37.5, lon = -77.6) # This location corresponds to Richmond, VA.

Getting weather file: USA_VA_Richmond.724010_TMY2.epw

... OK!

The downloaded EPW will be in the EPWs folder.

To load the data, use readWeatherFile. This reads EPWs, TMY meterological data, or even your own data as long as it follows TMY data format (With any time resoultion).

[7]:

# Read in the weather data pulled in above.

metdata = demo.readWeatherFile(epwfile, coerce_year=2001)

8760 line in WeatherFile. Assuming this is a standard hourly WeatherFile for the year for purposes of saving Gencumulativesky temporary weather files in EPW folder.

Coercing year to 2001

Saving file EPWs\metdata_temp.csv, # points: 8760

Calculating Sun position for Metdata that is right-labeled with a delta of -30 mins. i.e. 12 is 11:30 sunpos

5. Generate the Sky.#

Sky definitions can either be for a single time point with gendaylit function, or using gencumulativesky to generate a cumulativesky for the entire year.

[8]:

fullYear = True

if fullYear:

demo.genCumSky() # entire year.

else:

timeindex = metdata.datetime.index(pd.to_datetime('2001-06-17 12:0:0 -7'))

demo.gendaylit(timeindex) # Noon, June 17th (timepoint # 4020)

Loaded EPWs\metdata_temp.csv

message: Error! Solar altitude is -7 < -6 degrees and Idh = 13 > 10 W/m^2 on day 76 !Ibn is 0. Attempting to continue!

Error! Solar altitude is -7 < -6 degrees and Idh = 11 > 10 W/m^2 on day 78 !Ibn is 0. Attempting to continue!

Error! Solar altitude is -6 < -6 degrees and Idh = 14 > 10 W/m^2 on day 81 !Ibn is 0. Attempting to continue!

There were 4537 sun up hours in this climate file

Total Ibh/Lbh: 0.000000

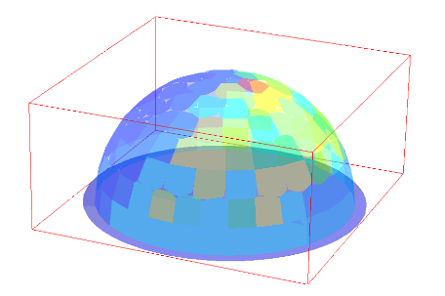

The method gencumSky calculates the hourly radiance of the sky hemisphere by dividing it into 145 patches. Then it adds those hourly values to generate one single cumulative sky. Here is a visualization of this patched hemisphere for Richmond, VA, US. Can you deduce from the radiance values of each patch which way is North?

Answer: Since Richmond is in the Northern Hemisphere, the modules face the south, which is where most of the radiation from the sun is coming. The north in this picture is the darker blue areas.

6. DEFINE a Module type#

You can create a custom PV module type. In this case we are defining a module named “Prism Solar Bi60”, in landscape. The x value defines the size of the module along the row, so for landscape modules x > y. This module measures y = 0.984 x = 1.695.

Modules in this example are 100% opaque. For drawing each cell, makeModule needs more inputs with cellLevelModule = True. You can also specify a lot more variables in makeModule like multiple modules, torque tubes, spacing between modules, etc. Reffer to the Module Documentation and read the following jupyter journals to explore all your options.

[9]:

module_type = 'test-module'

module = demo.makeModule(name=module_type,x=1.695, y=0.984)

print(module)

Module Name: test-module

Module test-module updated in module.json

Pre-existing .rad file objects\test-module.rad will be overwritten

{'x': 1.695, 'y': 0.984, 'z': 0.02, 'modulematerial': 'black', 'scenex': 1.705, 'sceney': 0.984, 'scenez': 0.1, 'numpanels': 1, 'bifi': 1, 'text': '! genbox black test-module 1.695 0.984 0.02 | xform -t -0.8475 -0.492 0 -a 1 -t 0 0.984 0', 'modulefile': 'objects\\test-module.rad', 'glass': False, 'offsetfromaxis': 0, 'xgap': 0.01, 'ygap': 0.0, 'zgap': 0.1}

In case you want to use a pre-defined module or a module you’ve created previously, they are stored in a JSON format in data/module.json, and the options available can be called with printModules:

[10]:

availableModules = demo.printModules()

Available module names: ['PrismSolar-Bi60', 'basic-module', 'test-module']

7. Make the Scene#

The sceneDicitonary specifies the information of the scene, such as number of rows, number of modules per row, azimuth, tilt, clearance_height (distance between the ground and lowest point of the module) and any other parameter.

Azimuth gets measured from N = 0, so for South facing modules azimuth should equal 180 degrees

[11]:

sceneDict = {'tilt':10,'pitch':3,'clearance_height':0.2,'azimuth':180, 'nMods': 20, 'nRows': 7}

To make the scene we have to create a Scene Object through the method makeScene. This method will create a .rad file in the objects folder, with the parameters specified in sceneDict and the module created above. You can alternatively pass a string with the name of the moduletype.

[12]:

scene = demo.makeScene(module,sceneDict)

8. COMBINE the Ground, Sky, and the Scene Objects#

Radiance requires an “Oct” file that combines the ground, sky and the scene object into it. The method makeOct does this for us.

[13]:

octfile = demo.makeOct(demo.getfilelist())

Created tutorial_1.oct

To see what files got merged into the octfile, you can use the helper method getfilelist. This is useful for advanced simulations too, specially when you want to have different Scene objects in the same simulation, or if you want to add other custom elements to your scene (like a building, for example)

[14]:

demo.getfilelist()

[14]:

['materials\\ground.rad',

'skies\\cumulative.rad',

'objects\\test-module_C_0.20000_rtr_3.00000_tilt_10.00000_20modsx7rows_origin0,0.rad']

9. ANALYZE and get Results#

Once the octfile tying the scene, ground and sky has been created, we create an Analysis Object. We first have to create an Analysis object, and then we have to specify where the sensors will be located with moduleAnalysis.

First let’s create the Analysis Object

[15]:

analysis = AnalysisObj(octfile, demo.basename)

Then let’s specify the sensor location. If no parameters are passed to moduleAnalysis, it will scan the center module of the center row:

[16]:

frontscan, backscan = analysis.moduleAnalysis(scene)

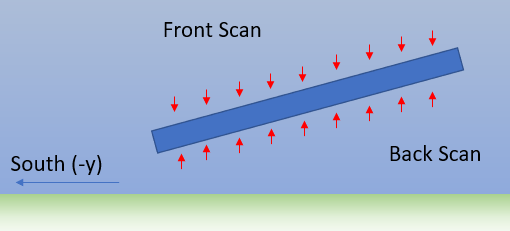

The frontscan and backscan include a linescan along a chord of the module, both on the front and back.

Analysis saves the measured irradiances in the front and in the back on the results folder. Prints out the ratio of the average of the rear and front irradiance values along a chord of the module.

Analysis saves the measured irradiances in the front and in the back on the results folder. Prints out the ratio of the average of the rear and front irradiance values along a chord of the module.

[17]:

results = analysis.analysis(octfile, demo.basename, frontscan, backscan)

Linescan in process: tutorial_1_Front

Linescan in process: tutorial_1_Back

Saved: results\irr_tutorial_1.csv

The results are also automatically saved in the results folder. Some of our input/output functions can be used to read the results and work with them, for example:

[18]:

load.read1Result('results\irr_tutorial_1.csv')

[18]:

| x | y | z | rearZ | mattype | rearMat | Wm2Front | Wm2Back | Back/FrontRatio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.791638e-17 | -0.391267 | 0.237768 | 0.216102 | a9.3.a0.test-module.6457 | a9.3.a0.test-module.2310 | 1624686.0 | 450289.3 | 0.277155 |

| 1 | 3.604893e-17 | -0.294362 | 0.254855 | 0.233189 | a9.3.a0.test-module.6457 | a9.3.a0.test-module.2310 | 1625372.0 | 338111.5 | 0.208021 |

| 2 | 2.418148e-17 | -0.197457 | 0.271942 | 0.250276 | a9.3.a0.test-module.6457 | a9.3.a0.test-module.2310 | 1626036.0 | 263294.4 | 0.161924 |

| 3 | 1.231403e-17 | -0.100552 | 0.289029 | 0.267363 | a9.3.a0.test-module.6457 | a9.3.a0.test-module.2310 | 1626700.0 | 220483.5 | 0.135540 |

| 4 | 4.465811e-19 | -0.003647 | 0.306116 | 0.284450 | a9.3.a0.test-module.6457 | a9.3.a0.test-module.2310 | 1627364.0 | 207700.7 | 0.127630 |

| 5 | -1.142087e-17 | 0.093258 | 0.323203 | 0.301537 | a9.3.a0.test-module.6457 | a9.3.a0.test-module.2310 | 1628028.0 | 210656.8 | 0.129394 |

| 6 | -2.328832e-17 | 0.190164 | 0.340290 | 0.318624 | a9.3.a0.test-module.6457 | a9.3.a0.test-module.2310 | 1629521.0 | 237394.5 | 0.145684 |

| 7 | -3.515577e-17 | 0.287069 | 0.357377 | 0.335711 | a9.3.a0.test-module.6457 | a9.3.a0.test-module.2310 | 1629566.0 | 278129.1 | 0.170677 |

| 8 | -4.702322e-17 | 0.383974 | 0.374464 | 0.352798 | a9.3.a0.test-module.6457 | a9.3.a0.test-module.2310 | 1629588.0 | 331617.1 | 0.203498 |

As can be seen in the results for the Wm2Front and WM2Back, the irradiance values are quite high. This is because a cumulative sky simulation was performed on step 5 , so this is the total irradiance over all the hours of the year that the module at each sampling point will receive. Dividing the back irradiance average by the front irradiance average will give us the bifacial gain for the year:

Assuming that our module from Prism Solar has a bifaciality factor (rear to front performance) of 90%, our bifacial gain is of:

[19]:

bifacialityfactor = 0.9

print('Annual bifacial ratio: %0.2f ' %( np.mean(analysis.Wm2Back) * bifacialityfactor / np.mean(analysis.Wm2Front)) )

Annual bifacial ratio: 0.16

10. View / Render the Scene#

If you used gencumsky or gendaylit, you can view the Scene by navigating on a command line to the folder and typing:

objview materials:nbsphinx-math:`ground`.rad objects:nbsphinx-math:`test`-module_C_0.20000_rtr_3.00000_tilt_10.00000_20modsx7rows_origin0,0.rad

[20]:

## Comment the ! line below to run rvu from the Jupyter notebook instead of your terminal.

## Simulation will stop until you close the rvu window

# !objview materials\ground.rad objects\test-module_C_0.20000_rtr_3.00000_tilt_10.00000_20modsx7rows_origin0,0.rad

This objview has 3 different light sources of its own, so the shading is not representative.

ONLY If you used gendaylit , you can view the scene correctly illuminated with the sky you generated after generating the oct file, with

rvu -vf views:nbsphinx-math:`front`.vp -e .01 tutorial_1.oct

[21]:

## Comment the line below to run rvu from the Jupyter notebook instead of your terminal.

## Simulation will stop until you close the rvu window

#!rvu -vf views\front.vp -e .01 tutorial_1.oct

The rvu manual can be found here: manual page here: http://radsite.lbl.gov/radiance/rvu.1.html

Or you can also use the code below from bifacial_radiance to generate an HDR rendered image of the scene. You can choose from front view or side view in the views folder:

[22]:

# Print a default image of the module and scene that is saved in /images/ folder. (new in v0.4.2)

scene.saveImage()

# Make a color render and falsecolor image of the scene.

analysis.makeImage('side.vp')

analysis.makeFalseColor('side.vp')

Scene image saved: images/Scene0_side.hdr

Generating visible render of scene

Generating scene in WM-2. This may take some time.

Saving scene in false color

This is how the False Color image stored in images folder should look like:

Files are saved as .hdr (high definition render) files. Try LuminanceHDR viewer (free) to view them, or https://viewer.openhdr.org/